Weaponising banks against men

Weaponising banks against men

– False allegations of financial abuse can now be used to freeze accounts.

Last week, Nigel Farage’s bank announced they were closing his accounts. The controversial UK politician had been with the bank for 40 years and was given no reason for the decision. Since then, Farage has tried unsuccessfully to get accounts at seven other banks.

Farage believes he has been targeted by the corporate world which “had not forgiven him for Brexit.” He claims that losing his bank account makes him a “non-person” and he is not sure he will be able to continue to live in the UK. Three members of Mr Farage’s immediate family have also recently had their accounts closed by UK banks, as have two former Brexit Party MPs. A vicar was also dropped as a customer after criticising his lender’s stance on LGBTQ+

There’s growing evidence that banking systems are now being used to exert social and political control. Remember the Canadian banks complying with Trudeau’s request to freeze the bank accounts of the truckers involved in the Canadian Freedom protests?

Alexandra Marshall in Spectator Australia warned banks are playing politics, tracking similar action by Paypal and other payment gateways now freezing accounts of journalists. She argues if we don’t do something about this, banking discrimination won’t be limited to political figures such as Farage or high-profile journalists but rather the banks will be coming for you.

Listen up, men. That’s happening right now.

Last week, the National Australia Bank (NAB) announced they plan to “cut off” customers found to be financial abusers, spelling out this means suspending, cancelling, or denying such people access to their accounts.

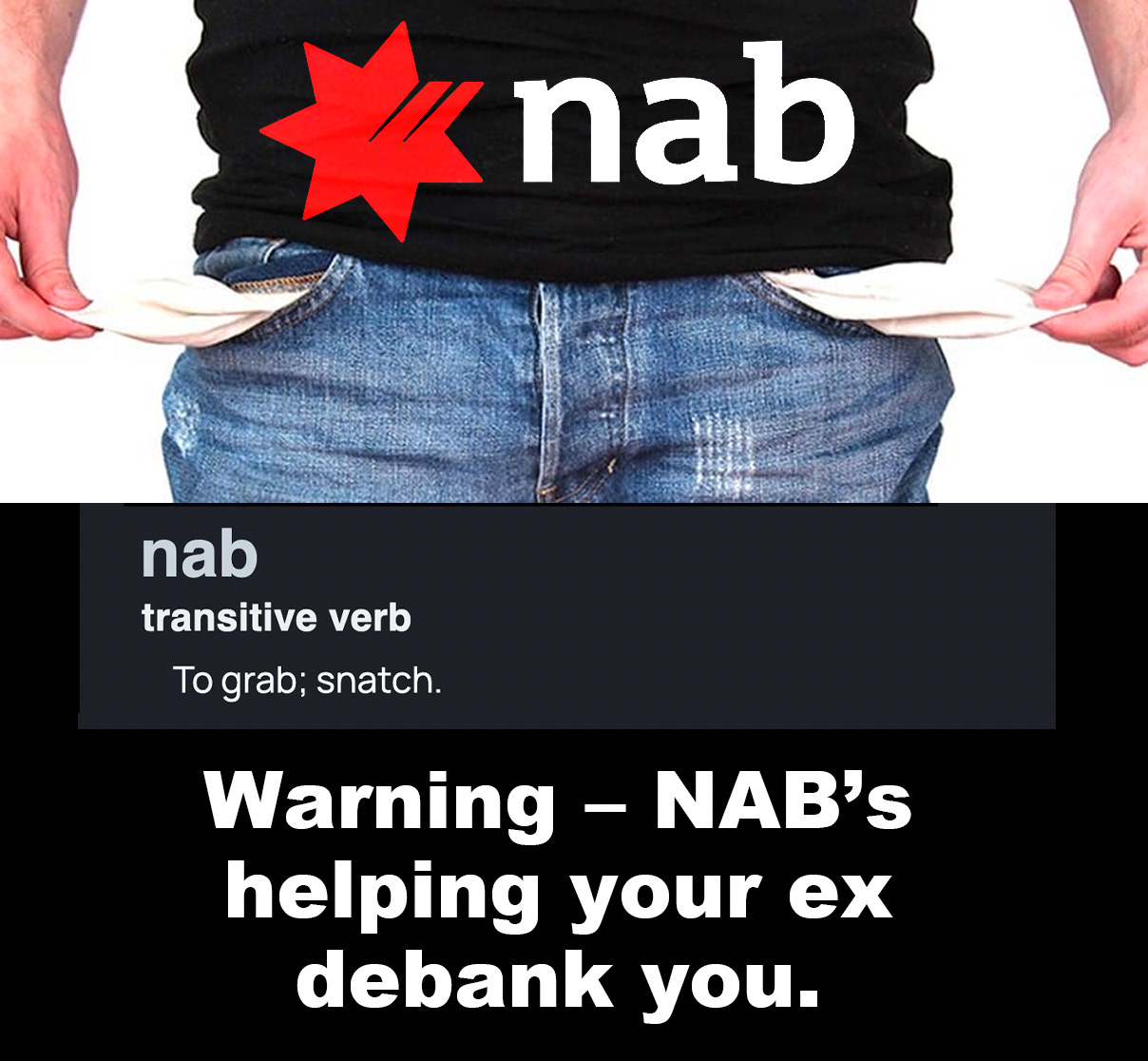

They call this “debanking” – cutting off the accounts of any man who is accused of being a financial abuser. How apt that the late, great comedian Barry Humphries once pointed out that NAB was another word for stealing!

But how will the banks prove they are dealing with actual perpetrators of this abuse? No problem. Believe women! Here’s the Australian Banking Association (ABA) cheerfully explaining that their guidelines on financial abuse specify no evidence is required if a woman claims her partner is an abuser: “The guideline recognises that banks don’t need legal evidence of domestic violence, such as an Apprehended Violence Order, to be able to offer assistance to customers,” said a ABA Executive, Diane Tate.

And what angry divorcing woman could resist destroying her ex-hubby’s credit rating? This ploy is not yet implemented, but rather simply recommended by the Centre for Women’s Economic Safety report, Designed to Disrupt, which maps out the feminist plans to use banks to tackle financial abuse. The feminists certainly see this as a great idea: “Consider the potential to develop a process to make an adverse credit report for a perpetrator of financial abuse which can be made concurrent to correction for victim-survivor, so that there is a material consequence that impacts on the ability to get future credit,” writes the author, UNSW Social Science professor Catherine Fitzpatrick.

Let that sink in. What we are talking about here is banks deliberately trashing a man’s credit rating as punishment when that person has not been convicted, charged, perhaps not even notified of the accusations. Doesn’t that take the cake?

That one is for the future, but right now we have NAB cutting off men’s accounts, with CommBank lining up to do so and Westpac likely to follow suit. These institutions never actually admit that the new apparatus is primarily targeting men. But even though Catherine Fitzpatrick in The Conversation claims about 1.6 million Australian women and 745,000 men have experienced economic or financial abuse, her article makes clear their true intentions: “challenging the acceptance of violence against women is essential to respond to specific gendered drivers of violence.”

The carefully orchestrated campaign enlisting our banks to tackle financial abuse has been promoted by the key organisations in the domestic violence industry which are shameless in their anti-male rhetoric. Comm Bank gave a cool half a million dollars a few years ago for research on financial abuse to UNSW’s Gendered Violence Research Network – the name is a bit of a give-away.

Here’s Anna Bligh, the CEO of the Australian Banking Association, which has been a major player in this impressive push: “This kind of behaviour is a form of domestic violence. It can be an enabler for partners to keep women trapped in abusive and often dangerous relationships.”

Women, women, women. And sure enough, the bank promotions on this subject never feature any male victims but tend to include numerous photographs of miserable, down-trodden women, often of various exotic ethnicities – yet the notion that particular ethnic groups are prone to financial abuse of their women naturally doesn’t get a mention. Given the competing sensitivities, virtue signalling in this territory demands a very careful tightrope walk.

So, are men being targeted already? It’s hard to tell but Andrew, one of my key researchers, reports an intriguing interrogation which took place after his partner Alison transferred a significant amount of money into his ING transaction account, which they’d planned to shift into a share trading account. Since the amount was beyond his normal transaction limit, Andrew called ING to arrange it. The operator put him on hold and then transferred him to her supervisor.

To his surprise, the supervisor quickly started grilling him about Alison’s transaction, asking about the nature of their relationship, how close they were, whether they had just broken up and other personal questions. Andrew explained they were friends and declined to answer further questions on the topic. She then threatened to freeze both his accounts with ING. He passed the phone to Alison and asked her to try to sort it out. After an intense conversation, Alison convinced the supervisor not to freeze his accounts. Andrew then took the phone back and said he wished to lodge an official complaint. It was some months later that Andrew received a call from ING called saying that, after investigation, the bank wished to apologise for what had happened.

There’s no telling what was really going on here. Perhaps the bank suspected Andrew of being a money mule or involved in some sort of scam. But the intrusive personal questions focussed on the relationship which implies this zealous bank official might have been following the official industry guidelines recommending banks be on the alert for signs they might be dealing with a perpetrator of financial abuse.

Normally, restricting a customer’s access to bank accounts would require a very high bar, such as evidence of criminality. But as this legal analysis from the Centre for Women’s Economic Safety points out, the feminists think they have this covered. They proudly announce that coming down the pipeline is their new magic bullet – coercive control: “In NSW, recent legislation provides for a new ‘coercive control’ offence. The NSW legislation criminalises abusive behaviour, including economic abuse, towards current and former intimate partners.”

That might just give the banks the muscle they need to justify their actions, which are certainly pushing the envelope when it comes to appropriate behaviour for a financial institution.

Clearly the banks’ lawyers believe they have found a way through any regulatory or legal hurdles. When I asked a former senior banking lawyer to examine what the banks are doing, he raised a concerning issue: “How do these banks defend themselves from charges that these are unfair contract terms in relation to financial products which are banned by the ASIC Act? Under recent amendments to unfair contract terms legislation to take effect in November 2023, a person such as a bank cannot include an unfair term in a standard form contract or rely on one that is already in place. Significantly increased penalties will apply for breach. One would have thought that these unilaterally imposed new terms which impose draconian consequences on affected consumers based solely on the bank’s view of the facts, with no apparent rights to appeal or prevent the action, are the very definition of unfair contract terms.”

You may like to include this vital question in letters of complaint to NAB and CommBank, particularly if you are a customer. And to the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA) But it’s even more important that you all use social media to alert people to what the banks are doing – here’s a meme you can use.

Please get back to me if you know of anyone who has been debanked. We are very keen to challenge the bank’s activities and need actual cases.

Note, there is an important real issue buried in the bank’s financial abuse initiatives, and that is elder abuse. Financial abuse is the most common form of elder abuse – Australian Institute of Family Studies research shows 2% of elders have suffered financial abuse in the last 12 months, which compares to 1.6% of people suffering this abuse from a cohabiting partner, as found in the ABS’s Personal Safety survey. But clearly most of the banks have other priorities.

One amusing sidenote. Even though the feminists realise they might need the muscle of new criminal coercive control laws, they do acknowledge this territory comes with the problem that women could also be identified as perpetrators. Here’s a CommBank document on legal responses to financial abuse which warns about the “misidentification” of financial abuse victims – which is code for women being nailed instead of men.

They are right to be concerned. Psychologists at the University of Central Lancashire, who carried out the major research available on male victims of coercive control, report financial abuse was a major issue for many of these men: “Half of male victims had their earnings controlled as a pattern of abuse which in some cases led to men not being able to purchase food or clothing. Men were also expected to take on the burden of all household finances as almost two thirds of the female perpetrators refused to contribute to household bills and over half refused to work even if able to. Similar to women, some male victims were prevented from going to work, whereas almost one in three male victims were forced to go to work even when unwell.”

Hmm, can you imagine the banks cutting off the accounts of women who refuse to work or contribute to household bills? That’s clearly not going to happen. This whole outrageous exercise is simply the latest feminist weapon for targeting men, introduced without government oversight, parliamentary scrutiny nor community consultation. It must be stopped.