‘How is this still happening?’: Family of man who took his own life over incorrect debt speaks out

The family of a Melbourne dad who took his own life a day after he was given an incorrect child support debt notice has called for the government’s controversial robo-debt system to be scrapped.

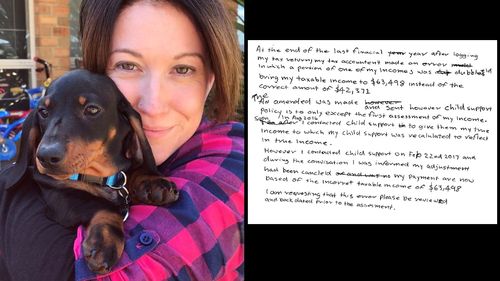

Anthony Searl, 38, was a charismatic TV cameraman who worked for Nine. He suicided two years ago after receiving the last in a series of letters from the Department of Human Service telling him he owed money, sister Wendy Searl said.

Last week, nine.com.au reported on the case of another man, 22-year-old Queenslander Jarrad Madgwick, whose mother said he took his own life just hours after finding out he had a Centrelink debt of $2000.

Ms Searl said she was devastated to hear the news of Mr Madgwick’s death.

“How is this still happening? I am absolutely shattered for this young man’s mother. His story sounds so similar to what happened with Anthony,” Ms Searl said.

Mr Searl’s suicide in March 2017 was the subject of a Department of Human Services and ombudsman’s review.

The Searl Review report in June 2017 led to legislative change and a government apology over “errors made” in his case.

However, Ms Searl said she was now left wondering what progress had been made by the Department of Human Services in the two years since her brother’s death.

Last week, Labor leader Bill Shorten called for the government’s automated system of raising debts, known as robo-debt, to be abolished.

A day later, the Senate announced it will hold a second inquiry into the robo-debt system, which matches tax records with inconsistencies in welfare payments.

The method of raising debts has been criticised for being inaccurate and for leaving vulnerable people with large amounts of unexpected debt.

In February this year, it was revealed that more than 2030 people had died after receiving a robot-debt notice, according to data released by the Department of Human Services.

Of the 2030 deaths, about one-fifth were aged under 35.

Data on the causes of death of the 2030 people were not collected by the department, but about a third, or 663, were classified as “vulnerable” and having complex needs such as mental illness, drug use or were victims of domestic violence.

Ms Searl said she believed robo-debt needed to go in order to prevent more lives being lost to suicide.

“My brother’s case was made so complicated and managed poorly by the department and that’s been confirmed by the investigation that took place,” she said.

“Questions should have been raised when the first person took their life after dealing with the department and here we are with over 2,000 lives lost.

“If they continue to hit our already vulnerable, then I’m convinced the number will rise. They owe the public a huge apology and should be held accountable for the damage they’ve caused.”

Ms Searl said her family would never recover from the loss of her brother, who was still “deeply missed”.

“Anthony was a lot Like Robin Williams, extremely animated and would burst into a character while telling you a joke or story,” she said.

“He was very sensitive, honest, loving and very family-oriented. Anthony was known by his work mates as the funny guy and turned hours of waiting around to be fun and lots of laughter.”

Mr Searl’s problems with the Department of Human Services began after his marriage broke down and he started to pay child support.

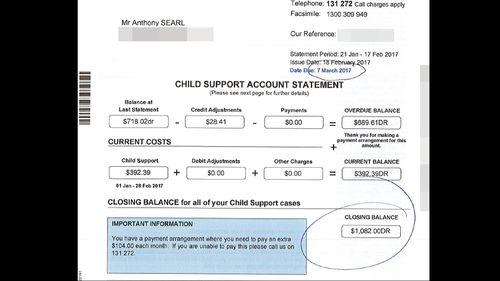

An error was made by his accountant, who accidentally doubled a portion of his income, inflating it by more than $20,000 per year.

This led to the department sending him a letter in January 2017 saying he owed more than $2000 in child support.

Mr Searl made repeated attempts to resolve the issue of Child Support having the wrong income information, but, under legislation at the time, the department was unable to accept amended tax returns.

“At one point, he rang up and was told that the error was fixed. But then it turned out it wasn’t,” Ms Searl said.

“He was really distressed. On one occasion he got a letter and then he had an acute panic attack. We took him to the doctors.”

“He just kept getting letters saying you owe this much money. He would make a payment of what he could afford and then he would get another letter saying you owe this much money.”

“Anthony was upset. His marriage had ended, he was a single parent, and then there were these financial burdens and expectations. We describe it as being the perfect storm.

“On the day before he took his life he got another letter.”

The legislation preventing the department from accepting amended tax returns has since been changed, partly in response to Mr Searl’s death.

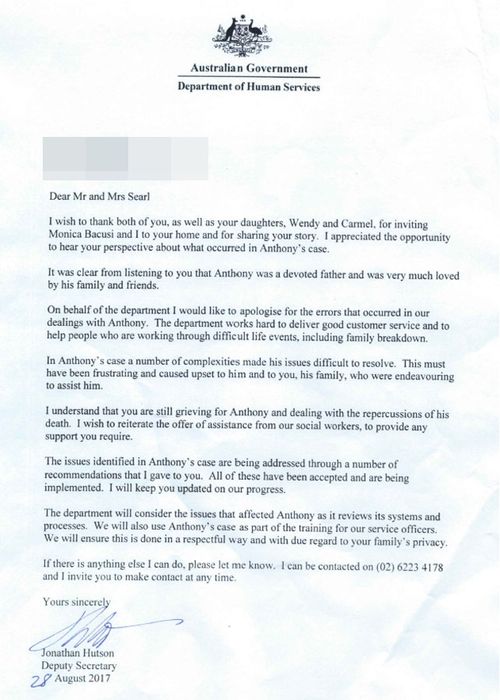

In a letter to the Searl family, the then Department of Human Services Deputy Secretary Jonathan Hutson apologised for the “errors that occurred in Anthony’s case”.

“In Anthony’s case a number of complexities made his issues difficult to resolve.”

Mr Searl’s case would be used as training for new child support officers, he wrote.

Ms Searl said that despite some changes being made by the department after her brother’s death, it was apparent there were still many broader issues that needed to be addressed by the department.

“Anthony’s story was going to be a case study for staff working at the department – know your signs, what can happen if things go wrong. I am shattered that we now have another family in the same boat,” she said.

In a statement provided to nine.com.au about Mr Searl’s case, Department of Human Services General Manager Hank Jongen said: “We take the wellbeing of our customers very seriously. We are deeply sorry for what this family have experienced, which is why the department extensively reviewed this case and made changes to improve the child support system and better support separated parents.”

“We don’t want people to ever feel that they are in a situation of helplessness. Support and help is always available from us and a wide range of government and community services.

“We strongly encourage anyone who is experiencing mental distress, or their concerned families or friends, to call 132 850 to speak to a social worker, or make an appointment to see one at a service centre.”

If you or someone you know is in need of support contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 46 36

Contact reporter Emily McPherson at emcpherson@nine.com.au.

© Nine Digital Pty Ltd 2019